VERKKOKIRJA

| Site: | MyCourses |

| Course: | MS-A0103 - Differentiaali- ja integraalilaskenta 1 (ELEC1, ENG1), Luento-opetus, 4.9.2023-18.10.2023 |

| Book: | VERKKOKIRJA |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 19 February 2025, 12:30 AM |

Description

Differentiaali- ja integraalilaskenta - verkkokirja, tekijä Pekka Alestalo

Englanninkielisen MOOC-kurssin luentomateriaali, joka perustuu tämän kurssin luentoihin. Mukana on interaktiivisia JSXGraph-kuvia, joita ei ole suomenkielisissä luentokalvoissa. Toistaiseksi vain luvut 1-5, 7 ja 9 ovat suomeksi.

1. Jonot

Sisältö

- Peruskäsitteet

- Tärkeitä jonoja

- Suppeneminen ja raja-arvo

Jonot

Tämä luku sisältää tärkeimmät jonoihin liittyvät käsitteet. Käsittelemme käytännössä vain reaalilukujonohin liittyviä asioita.

Huom. Koska  on järjestetty joukko, niin myös jonon termeillä

on järjestetty joukko, niin myös jonon termeillä  on vastaava järjestys. Sen sijaan joukon alkioilla ei yleisessä tapauksessa

ole määrättyä järjestystä.

on vastaava järjestys. Sen sijaan joukon alkioilla ei yleisessä tapauksessa

ole määrättyä järjestystä.

Määritelmä: Jonon termit ja indeksit

Jonoille voidaan käyttää myös merkintöjä

Funktion  perusteella jokaiseen jonon termiin liittyy yksikäsitteinen lukua

perusteella jokaiseen jonon termiin liittyy yksikäsitteinen lukua  to each term. Se merkitään alaindeksinä ja sitä kutsutaan vastaavan jonon termin

indeksiksi; jokainen jonon termi voidaan siis tunnistaa sen indeksin avulla.

to each term. Se merkitään alaindeksinä ja sitä kutsutaan vastaavan jonon termin

indeksiksi; jokainen jonon termi voidaan siis tunnistaa sen indeksin avulla.

Esimerkkejä

Esimerkki 1: Luonnollisten lukujen jono

Jono  , joka on määritelty kaavalla

, joka on määritelty kaavalla  on nimeltään luonnollisten lukujen jono. Sen ensimmäiset termit ovat:

on nimeltään luonnollisten lukujen jono. Sen ensimmäiset termit ovat:

![]()

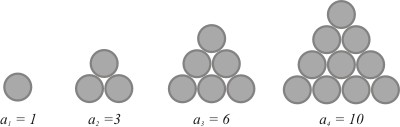

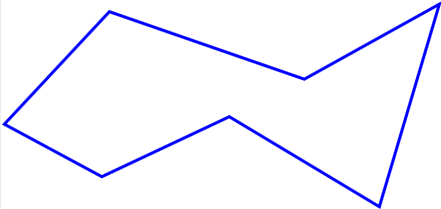

Esimerkki 2: Kolmiolukujen jono

Kolmioluvut saavat nimensä seuraavasta geometrisesta periaatteesta: Asetetaan sopiva määrä kolikoita niin, että syntyy yhä suurempia tasasivuisia kolmioita:

Ensimmäisen kolikon alle lisätään kaksi kolikkoa, jolloin toisessa vaiheessa saadaan  kolikkoa. Seuraavaksi tämän kolmion alle lisätään kolme uutta kolikkoa, joita on nyt yhteensä

kolikkoa. Seuraavaksi tämän kolmion alle lisätään kolme uutta kolikkoa, joita on nyt yhteensä  .

Etenemällä samaan tapaan huomataan, että esimerkiksi 10. kolmioluku saadaan laskemalla yhteen 10 ensimmäistä luonnollista lukua:

.

Etenemällä samaan tapaan huomataan, että esimerkiksi 10. kolmioluku saadaan laskemalla yhteen 10 ensimmäistä luonnollista lukua:

Yleinen kaava kolmiolukujonon termeille on

Yleinen kaava kolmiolukujonon termeille on  . Kolmioluvuille käytetään yleensä merkintää

. Kolmioluvuille käytetään yleensä merkintää  (T = 'Triangle').

(T = 'Triangle').

Tämä motivoi seuraavaan määritelmään:

Määritelmä: Summajono

Olkoon  jono joukossa

jono joukossa  , jossa on määritelty yhteenlasku. Merkitään

, jossa on määritelty yhteenlasku. Merkitään

Symboli

Symboli  on kreikkalainen kirjain sigma. Summausindeksi

on kreikkalainen kirjain sigma. Summausindeksi  kasvaa

alkuarvosta 1 loppuarvoon

kasvaa

alkuarvosta 1 loppuarvoon  .

.

Summajono saadaan siis alkuperäisestä jonosta laskemalla alkupään termejä yhteen aina yksi termi eteenpäin. Varsinkin sarjojen kohdalla käytetään nimeä osasummajono.

Kolmiolukujen yleinen kaava voidaan siis kirjoittaa muodossa

ja kyseessä on luonnollisten lukujen jonon summajono.

ja kyseessä on luonnollisten lukujen jonon summajono.

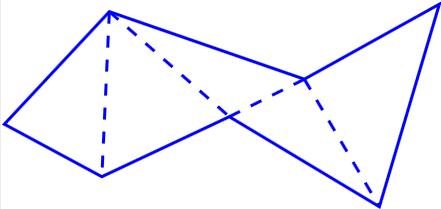

Esimerkki 3: Neliölukujen jono

Neliölukujen jono  määritellään kaavalla

määritellään kaavalla  . Tämän jonon termejä voidaan havainnollistaa asettelemalla kolikoita neliön muotoon.

. Tämän jonon termejä voidaan havainnollistaa asettelemalla kolikoita neliön muotoon.

Yksi mielenkiintoinen havainto on se, että kahden peräkkäisen kolmioluvun summa on aina neliöluku. Esimerkiksi  ja

ja  . Yleisesti määritelmiä käyttämällä

voidaan osoittaa, että

. Yleisesti määritelmiä käyttämällä

voidaan osoittaa, että

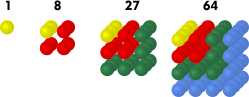

Esimerkki 4: Kuutiolukujen jono

Määritelmä: Erotusjono (differenssijono)

Jonon  termeistä voidaan myös muodostaa peräkkäisten termien erotuksia:

termeistä voidaan myös muodostaa peräkkäisten termien erotuksia:

on nimeltään alkuperäisen jonon

on nimeltään alkuperäisen jonon  ensimmäinen differenssijono.

ensimmäinen differenssijono.

Ensimmäisen differenssijonon ensimmäinen differenssijono on alkuperäisen jonon toinen differenssijono. sequence. Vastaavalla tavalla määritellään jonon  differenssijono.

differenssijono.

Esimerkki 6.

Eräitä tärkeitä jonoja

Eräät jonot ovat keskeisiä monille matemaattisille malleille ja niiden käytännön sovelluksille muilla aloilla kuten luonnontieteissä ja taloustieteissä.) Seuraavassa tarkastellaan kolme tällaista jonoa: aritmeettinen jono, geometrinen jono ja Fibonaccin lukujono.

Aritmeettinen jono

Aritmeettinen jono voidaan määritellä monella eri tavalla:Määritelmä A: Aritmeettinen jono

Jono  on aritmeettinen, jos sen peräkkäisten termien erotus

on aritmeettinen, jos sen peräkkäisten termien erotus  on vakio, t.s.

on vakio, t.s.

Huomautus: Aritmeettisen jonon eksplisiittinen kaava seuraa suoraan määritelmästä A:

Aritmeettisen jonon

Aritmeettisen jonon  termi voidaan laskea myös palautuskaavan (eli rekursiokaavan) avulla:

termi voidaan laskea myös palautuskaavan (eli rekursiokaavan) avulla:

Määritelmä B: Aritmeettinen jono

Jono  on aritmeettinen jono, jos sen ensimmäinen differenssijono on vakiojono.

on aritmeettinen jono, jos sen ensimmäinen differenssijono on vakiojono.

Tämä määritelmä selventää myös aritmeettisen jonon nimen: Kolmen peräkkäisen termin keskimmäinen luku on kahden muun termin aritmeettinen keskiarvo; esimerkiksi

Geometrinen jono

Myös geometrisella jonolla on useita erilaisia määritelmiä:

Määritelmä: Geometrinen jono

Jono  on geometrinen, jos kahden präkkäisen termin suhde on aina vakio

on geometrinen, jos kahden präkkäisen termin suhde on aina vakio  , t.s.

, t.s.

Huomautus. Palautuskaava  geometrisen jonon termeille ja myös eksplisiittinen lauseke

geometrisen jonon termeille ja myös eksplisiittinen lauseke

seuraavat suoraan määritelmästä.

seuraavat suoraan määritelmästä.

Myös tässä jonon nimityksellä on looginen tausta: Kolmen peräkkäisen termin keskimmäinen luku on aina kahden muun termin geometrinen keskiarvo; esimerkiksi

Esimerkki 2.

Olkoon  ja

ja  . Jono

. Jono  , jolle

, jolle  , eli

, eli

on geometrinen jono. Jos

on geometrinen jono. Jos  ja

ja  , niin jono on aidosti

kasvava. Jos

, niin jono on aidosti

kasvava. Jos  ja

ja  , niin se on aidosti vähenevä. Jonon alkioiden muodostama joukko

, niin se on aidosti vähenevä. Jonon alkioiden muodostama joukko  on äärellinen, jos

on äärellinen, jos  (jolloin sen ainoa alkio on

(jolloin sen ainoa alkio on  ), muuten tämä joukko on ääretön.

), muuten tämä joukko on ääretön.

Fibonaccin jono

Fibonaccin lukujono on kuuluisa sen biologisten sovellusten vuoksi. Se esiintyy mm.eliöiden populaation kasvun yhteydessä ja kasvien rakenteessa. Palautuskaavaan perustuva määritelmä on seuraava:

Määritelmä: Fibonaccin jono

Olkoon  ja

ja

kun

kun  . Jono

. Jono  on Fibonaccin lukujono. Jonon termit ovat Fibonaccin lukuja.

on Fibonaccin lukujono. Jonon termit ovat Fibonaccin lukuja.

Jonon nimen takana on italialainen Leonardo Pisano (1200-luvulla), latinalaiselta nimeltään Filius Bonacci. Hän tutki kaniparien lisääntymistä idealisoidussa tilanteessa, jossa kanit eivät kuole ja kaikki vanhat sekä uudet parit

lisääntyvät säännöllisin väliajoin. Näin hän päätyi jonoon

Esimerkki 3.

Auringonkukan kukat muodostuvat kahdesta spiraalista, jotka aukeavat keskeltä vastakkaisiin suuntiin: 55 spiraalia myötäpäivään ja 34 vastapäivään.

Myös ananashedelmän pinta käyttäytyy samalla tavalla. Siinä on 21 spiraalia yhteen suuntaan ja 34 vastakkaiseen. Myös joissakin kaktuksissa ja havupuiden kävyissä on samanlaisia rakenteita.

Suppeneminen, hajaantuminen ja raja-arvo

Tässä luvussa käsitellään jonon suppenemista. Aloitamme nollajonon käsitteestä ja siirrymme sen avulla yleiseen suppenemisen käsitteeseen.

Huomautus: Itseisarvo joukossa

Itseisarvofunktio  on keskeisessä asemassa jonojen suppenemisen tutkimisessa. Seuraavassa käydään läpi sen tärkeimmät ominaisuudet:

on keskeisessä asemassa jonojen suppenemisen tutkimisessa. Seuraavassa käydään läpi sen tärkeimmät ominaisuudet:

Lause: Itseisarvon laskusääntöjä

Kohdat 1.-3. Results follow directly from the definition and by dividing it up into separate cases of the different signs of  and

and

Kohta 4. Tämä kohta voidaan todistaa neliöön korottamalla tai tutkimalla kaikki eri vaihtoehdot kuten alla.

Tapaus 1.

Olkoot  . Silloin

. Silloin

ja kaava pätee.

ja kaava pätee.

Tutkitaan lopuksi tapaus  and

and  , joka jakaantuu kahteen alakohtaan:

, joka jakaantuu kahteen alakohtaan:

Jos  ja

ja  , niin väite seuraa samalla periaatteella kuin tapauksessa 3, kun vaihdetaan keskenään

, niin väite seuraa samalla periaatteella kuin tapauksessa 3, kun vaihdetaan keskenään  ja

ja

.

.

Nollajono

Esimerkki 1.

Jono  , joka on määritelty kaavalla

, joka on määritelty kaavalla  , eli

, eli  on nimeltään harmoninen jono. Jonon termit ovat positiivisia kaikilla

on nimeltään harmoninen jono. Jonon termit ovat positiivisia kaikilla  , mutta indeksin

, mutta indeksin  kasvaessa jonon termit pienenevät yhä lähemmäksi

nollaa.

kasvaessa jonon termit pienenevät yhä lähemmäksi

nollaa.

Jos esimerkiksi  , niin valinnalla

, niin valinnalla  pätee

pätee  aina, kun

aina, kun  .

.

Harmoninen jono suppenee kohti nollaa

Esimerkki 2.

Tarkastellaan jonoa  Olkoon

Olkoon  . Tällöin valinnalla

. Tällöin valinnalla  kaikille termeille

kaikille termeille  , joissa

, joissa  , pätee

, pätee  .

.

Note. Tutkittaessa nollajono-ominaisuutta täytyy tutkia mielivaltaista lukua  , jolle

, jolle  . Sen jälkeen

yritetään valita sellainen indeksi

. Sen jälkeen

yritetään valita sellainen indeksi  , josta alkaen jokainen

, josta alkaen jokainen  on pienempi kuin

on pienempi kuin  .

.

Esimerkki 3.

Kerrointen  vuoksi jonon kaksi peräkkäistä termiä ovat aina erimerkkisiä; tällaista jonoa kutsutaan yleisemmin vuorottelevaksi jonoksi.

vuoksi jonon kaksi peräkkäistä termiä ovat aina erimerkkisiä; tällaista jonoa kutsutaan yleisemmin vuorottelevaksi jonoksi.

Osoitetaan, että kyseessä on nollajono. Määritelmän mukaan jokaista  täytyy vastata sellainen

täytyy vastata sellainen  , että epäyhtälö

, että epäyhtälö

pätee kaikille niille termeille

pätee kaikille niille termeille  , joissa

, joissa  .

.

Lause: Nollajonojen ominaisuuksia

Parts 1 and 2. If  is a zero sequence, then according to the definition there is an index

is a zero sequence, then according to the definition there is an index  , such that

, such that  for every

for every  and an arbitrary

and an arbitrary  . But then we have

. But then we have  ; this

proves parts 1 and 2 are correct.

; this

proves parts 1 and 2 are correct.

Part 3. If  , then the result is trivial. Let

, then the result is trivial. Let  and choose

and choose  such that

such that

for all

for all  . Rearranging we get:

. Rearranging we get:

Part 4.

Because  is a zero sequence, by the definition we have

is a zero sequence, by the definition we have  for all

for all  . Analogously,

for the zero sequence

. Analogously,

for the zero sequence  there is a

there is a  with

with  for all

for all  .

.

Then for all  it follows (using the triangle inequality) that:

it follows (using the triangle inequality) that:

Suppeneminen ja hajaantuminen

Nollajonoja voidaan käyttää tutkimaan jonojen suppenemista yleisemmin:

Esimerkki 4.

Tarkastellaan jonoa  , jossa

, jossa

Laskemalla jonon termejä suurilla

Laskemalla jonon termejä suurilla  , huomataan, että ilmeisesti

, huomataan, että ilmeisesti  , kun

, kun

, joten jonon raja-arvo voisi olla

, joten jonon raja-arvo voisi olla  .

.

For a rigorous proof, we show that for every  there exists an index

there exists an index  , such that for every term

, such that for every term  with

with  the following relationship holds:

the following relationship holds:

Firstly we estimate the inequality:

Now, let  be an arbitrary constant. We then choose the index

be an arbitrary constant. We then choose the index  , such that

, such that

Finally from the above inequality we have:

Finally from the above inequality we have:

Thus we have proven the claim and so by definition

Thus we have proven the claim and so by definition  is

the limit of the sequence.

is

the limit of the sequence.

Jos jono suppenee, niin sillä voi olla vain yksi raja-arvo.

Lause: Raja-arvon yksikäsitteisyys

Oletetaan, että jono  suppenee kohti raja-arvoa

suppenee kohti raja-arvoa  ja kohti raja-arvoa

ja kohti raja-arvoa  .

Silloin

.

Silloin  .

.

Assume  ; choose

; choose  with

with  Then in particular

Then in particular ![[a-\varepsilon,a+\varepsilon]\cap[b-\varepsilon,b+\varepsilon]=\emptyset. [a-\varepsilon,a+\varepsilon]\cap[b-\varepsilon,b+\varepsilon]=\emptyset.](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/4bac60723e473d9697be98685ce7659a.gif)

Because  converges to

converges to  , there is, according to the definition of convergence, a index

, there is, according to the definition of convergence, a index  with

with  for

for  Furthermore, because

Furthermore, because  converges to

converges to  there is also a

there is also a  with

with  for

for  For

For

we have:

we have:

Consequently we have obtained

Consequently we have obtained  , which is a contradiction as

, which is a contradiction as  .

Therefore the assumption must be wrong, so

.

Therefore the assumption must be wrong, so  .

.

Suppenevien jonojen ominaisuuksia

Lause: Laskusääntöjä

Olkoot  ja

ja  suppenevia jonoja, joille

suppenevia jonoja, joille  ja

ja  .

Silloin kaikille

.

Silloin kaikille  pätee:

pätee:

Sanallisesti: Suppenevien jonojen summat ja tulot ovat suppenevia jonoja.

Part 1. Let  . We must show, that for all

. We must show, that for all  it follows that:

it follows that:

The left hand side we estimate using:

The left hand side we estimate using:

Because  and

and  converge, for each given

converge, for each given  it holds true that:

it holds true that:

Therefore

for all numbers

for all numbers  . Therefore the sequence

. Therefore the sequence

is a zero sequence and the desired inequality is shown.

is a zero sequence and the desired inequality is shown.

Part 2. Let  . We have to show, that for all

. We have to show, that for all

Furthermore an estimation of the left hand side follows:

Furthermore an estimation of the left hand side follows:

We choose a number

We choose a number  , such that

, such that  for all

for all  and

and  . Such a value of

. Such a value of  exists by the Theorem of convergent sequences being bounded. We can then use the estimation:

exists by the Theorem of convergent sequences being bounded. We can then use the estimation:

For all

For all  we have

we have

and

and  , and - putting everything together - the desired inequality it shown.

, and - putting everything together - the desired inequality it shown.

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

bars.push(newbar(k));

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* fibonacci sequence */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox03', {

boundingbox: [-1, 40, 10, -5],

axis: false,

shownavigation: false,

showcopyright: false

});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [

[0, 0],

[1, 0]

], {

straightFirst: false,

highlight: false,

drawZero: true,

ticks: {

drawLabels: false,

minorTicks: 0,

majorHeight: 15,

label: {

highlight: false,

offset: [0, -15]

}

}

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [

[0, 0],

[0, 1]

], {

straightFirst: false,

highlight: false,

ticks: {

minorTicks: 0,

majorHeight: 15,

label: {

offset: [-15, 0],

position: 'lrt',

highlight: false

}

}

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() {

return 1;

};

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() {

return 5;

};

var a_k = [1, 1];

var newbar = function(k) {

var y;

if (k - 1 > a_k.length - 1) {

y = a_k[k - 3] + a_k[k - 2];

a_k.push(y);

} else {

y = a_k[k - 1];

}

return board.create('polygon', [

[k - 1 / 4, 0],

[k + 1 / 4, 0],

[k + 1 / 4, y],

[k - 1 / 4, y]

], {

vertices: {

visible: false

},

borders: {

strokeColor: 'black',

strokeOpacity: .6,

highlight: false

},

fillColor: '#b2caeb',

fixed: true,

highlight: false

});

}

var bars = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

const k = i + 1;

board.create('text', [k - .1, -.6, function() {

return '

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

bars.push(newbar(k));

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* fibonacci sequence */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox03', {

boundingbox: [-1, 40, 10, -5],

axis: false,

shownavigation: false,

showcopyright: false

});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [

[0, 0],

[1, 0]

], {

straightFirst: false,

highlight: false,

drawZero: true,

ticks: {

drawLabels: false,

minorTicks: 0,

majorHeight: 15,

label: {

highlight: false,

offset: [0, -15]

}

}

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [

[0, 0],

[0, 1]

], {

straightFirst: false,

highlight: false,

ticks: {

minorTicks: 0,

majorHeight: 15,

label: {

offset: [-15, 0],

position: 'lrt',

highlight: false

}

}

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() {

return 1;

};

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() {

return 5;

};

var a_k = [1, 1];

var newbar = function(k) {

var y;

if (k - 1 > a_k.length - 1) {

y = a_k[k - 3] + a_k[k - 2];

a_k.push(y);

} else {

y = a_k[k - 1];

}

return board.create('polygon', [

[k - 1 / 4, 0],

[k + 1 / 4, 0],

[k + 1 / 4, y],

[k - 1 / 4, y]

], {

vertices: {

visible: false

},

borders: {

strokeColor: 'black',

strokeOpacity: .6,

highlight: false

},

fillColor: '#b2caeb',

fixed: true,

highlight: false

});

}

var bars = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

const k = i + 1;

board.create('text', [k - .1, -.6, function() {

return ' ';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

bars.push(newbar(k));

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

strokeColor: '#2183de',

fontSize: 13,

fixed: true,

highlight: false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

board.create('point', [i, 1 / i], {

size: 4,

name: '',

strokeWidth: .5,

strokeColor: 'black',

face: 'diamond',

fillColor: '#cf4490',

fixed: true

});

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

bars.push(newbar(k));

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

strokeColor: '#2183de',

fontSize: 13,

fixed: true,

highlight: false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

';

}], {

useMathJax: true,

fixed: true,

strokeOpacity: 0.6

});

board.create('point', [i, 1 / i], {

size: 4,

name: '',

strokeWidth: .5,

strokeColor: 'black',

face: 'diamond',

fillColor: '#cf4490',

fixed: true

});

}

board.fullUpdate();

})();

2. Sarjat

Suppeneminen

Suppeneminen

Jonosta  voidaan muodostaa sen osasummia asettamalla

voidaan muodostaa sen osasummia asettamalla

Jos osasumminen jonolla  on raja-arvo

on raja-arvo  , niin luvuista

, niin luvuista  muodostettu sarja suppenee ja sen summa on

muodostettu sarja suppenee ja sen summa on  . Tällöin merkitään

. Tällöin merkitään

Sarjan hajaantuminen

Sarja, joka ei suppene, on hajaantuva. Tämä voi tapahtua kolmella eri tavalla:

- sarjan osasummat kasvavat rajatta kohti ääretöntä

- sarjan osasummat pienenevät rajatta kohti miinus ääretöntä

- osasummien jono heilahtelee niin, ettei sillä ole raja-arvoa.

Hajaantuvan sarjan kohdalla merkintä  ei oikeastaan tarkoita mitään (se ei ole reaaliluku). Tällöin voidaan tulkita, että merkintä tarkoittaa osasummien jonoa, joka on aina hyvin määritelty.

ei oikeastaan tarkoita mitään (se ei ole reaaliluku). Tällöin voidaan tulkita, että merkintä tarkoittaa osasummien jonoa, joka on aina hyvin määritelty.

Perustuloksia

Geometrinen sarja

Geometrinen sarja

suppenee, jos

suppenee, jos  (tai

(tai  ), jolloin sen summa on

), jolloin sen summa on  . Jos

. Jos  , niin sarja hajaantuu.

, niin sarja hajaantuu.

Laskusääntöjä

Suppenevien sarjojen ominaisuuksia:

Todistus. Nämä seuraavat vastaavista tuloksista jonojen raja-arvolle.

Huomautus: Sarjoilla ei ole jonojen kaltaista tulosääntöä, koska jo kahden termin summille

Tulosäännön oikea muoto on sarjojen Cauchy-tulo, jossa myös ristitermit otetaan huomioon.

Tulosäännön oikea muoto on sarjojen Cauchy-tulo, jossa myös ristitermit otetaan huomioon.

Katso esimerkiksi https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cauchy_product

Huomautus: Ominaisuutta  ei voi käyttää sarjan suppenemisen osoittamiseen; vrt. seuraavat esimerkit.

Tämä on eräs yleisimmistä päättelyvirheistä sarjojen kohdalla!

ei voi käyttää sarjan suppenemisen osoittamiseen; vrt. seuraavat esimerkit.

Tämä on eräs yleisimmistä päättelyvirheistä sarjojen kohdalla!

Esimerkki

Ratkaisu. Sarjan yleisen termin raja-arvo on

Koska raja-arvo ei ole nolla, niin sarja hajaantuu.

Koska raja-arvo ei ole nolla, niin sarja hajaantuu.

Tämän klassisen tuloksen todisti ensimmäisenä 14. vuosisadalla Nicole Oresme, jonka jälkeen monia muitakin perusteluja on keksitty. Tässä esimerkkinä kaksi erilaista päättelyä.

i) Alkeellinen todistus. Oletetaan, että sarja suppenee ja yritetään johtaa tästä ristiriita. Olkoon siis  harmonisen sarjan summa:

harmonisen sarjan summa:  . Tällöin

. Tällöin

Selvästi

Selvästi

joten

joten

Päädyimme siis epäyhtälöön

Päädyimme siis epäyhtälöön  , joka on ristiriita. Alkuperäinen oletus suppenemisesta on siis väärä, joten sarja hajaantuu.

, joka on ristiriita. Alkuperäinen oletus suppenemisesta on siis väärä, joten sarja hajaantuu.

ii) Todistus integraalin avulla: Pylvään korkeuksia  vastaavan histogrammin alapuolelle jää funktion

vastaavan histogrammin alapuolelle jää funktion  kuvaaja, joten pinta-aloja vertaamalla saadaan

kuvaaja, joten pinta-aloja vertaamalla saadaan

kun

kun  .

.

Positiiviset sarjat

Sarjan summan laskeminen on usein vaikeata ja monesti jopa mahdotonta, jos vaatimuksena on summan eksplisiittinen lauseke. Moniin sovelluksiin riittää myös summan likiarvo, mutta sitä ennen olisi syytä selvittää, onko sarja suppeneva vai hajaantuva.

Sarja  on positiivinen (tai positiiviterminen), jos

on positiivinen (tai positiiviterminen), jos  kaikilla

kaikilla  .

.

Positiivisten sarjojen suppeneminen on hyvin selväpiirteistä:

Lause 2.

Positiivinen sarja suppenee täsmälleen silloin, kun sen osasummien jono on ylhäältä rajoitettu.

Syy: Osasummien jono on nouseva.

Esimerkki

Osoita, että superharmonisen sarjan

osasummille pätee

osasummille pätee  kaikilla

kaikilla  , joten sarja suppenee.

, joten sarja suppenee.

Ratkaisu. Ratkaisu perustuu epäyhtälöön

kun

kun  , koska sen mukaan

, koska sen mukaan

kaikilla

kaikilla  .

.

Tämän päättelyn voi tehdä myös integraalin avulla.

Leonhard Euler selvitti vuonna 1735, että sarjan summa on  . Perusteluna hän käytti sinifunktion sarja- ja tulokehitelmien vertailua.

. Perusteluna hän käytti sinifunktion sarja- ja tulokehitelmien vertailua.

Itseinen suppeneminen

Lause 3.

Itseisesti suppeneva sarja suppenee (tavallisessa mielessä) ja

Tämä on erikoistapaus majoranttiperiaatteesta, josta lisää myöhemmin.

Oletetaan, että  suppenee. Tarkastellaan erikseen sarjan

suppenee. Tarkastellaan erikseen sarjan  positiivista ja negatiivista osaa: Olkoon

positiivista ja negatiivista osaa: Olkoon  Koska

Koska  , niin positiiviset sarjat

, niin positiiviset sarjat  ja

ja  suppenevat lauseen 2 perusteella. Lisäksi

suppenevat lauseen 2 perusteella. Lisäksi  , joten

, joten  suppenee kahden suppenevan sarjan erotuksena.

suppenee kahden suppenevan sarjan erotuksena.

Esimerkki

Tutki vuorottelevan (= etumerkit vaihtelevat vuorotellen + ja -) sarjan  suppenemista.

suppenemista.

Ratkaisu. Koska

ja superharmoninen sarja

ja superharmoninen sarja

suppenee, niin tutkittava sarja suppenee itseisesti, ja sen vuoksi myös tavallisessa mielessä.

suppenee, niin tutkittava sarja suppenee itseisesti, ja sen vuoksi myös tavallisessa mielessä.

Vuorotteleva harmoninen sarja

Itseinen suppeneminen ei kuitenkaan tarkoita samaa kuin tavallinen suppeneminen:

Esimerkki

Vuorotteleva harmoninen sarja

suppenee, mutta ei itseisesti.

suppenee, mutta ei itseisesti.

(Idea) Piirretään osasummajonon  kuvaaja, josta huomataan, että parillisten ja parittomien indeksien osasummat

kuvaaja, josta huomataan, että parillisten ja parittomien indeksien osasummat  ja

ja  ovat monotonisia ja suppenevat kohti samaa raja-arvoa.

ovat monotonisia ja suppenevat kohti samaa raja-arvoa.

Sarjan summa on  , joka saadaan selville integroimalla geometrisen sarjan summakaavaa.

, joka saadaan selville integroimalla geometrisen sarjan summakaavaa.

pisteet on yhdistetty janoilla havainnollisuuden vuoksi

Suppenemistestejä

Vertailutestit

Edelliset tarkastelut yleistyvät seuraavalla tavalla:

Esimerkki

Ratkaisu. Koska kaikilla

kaikilla  , niin ensimmäinen sarja suppenee majoranttiperiaatteen nojalla.

, niin ensimmäinen sarja suppenee majoranttiperiaatteen nojalla.

Toisaalta  kaikilla

kaikilla  , joten toisella sarjalla on hajaantuva harmoninen minorantti, joten se hajaantuu.

, joten toisella sarjalla on hajaantuva harmoninen minorantti, joten se hajaantuu.

Suhdetesti

Käytännössä eräs parhaista tavoista tutkia suppenemista on suhdetesti, jossa sarjan peräkkäisten termien käyttäytymistä verrataan sopivaan geometriseen sarjaan:

Suhdetestin raja-arvomuoto

(Idea) Geometriselle sarjalle kahden peräkkäisen termin suhde on täsmälleen  . Suhdetestin mukaan muidenkin sarjojen suppenemista voidaan (usein) tutkia samalla periaatteella, kun

suhdeluku

. Suhdetestin mukaan muidenkin sarjojen suppenemista voidaan (usein) tutkia samalla periaatteella, kun

suhdeluku  korvataan tällä raja-arvolla.

korvataan tällä raja-arvolla.

Valitaan raja-arvon määritelmässä  . Silloin jostakin indeksistä

. Silloin jostakin indeksistä  alkaen pätee

alkaen pätee

ja väite seuraa lauseesta 4.

ja väite seuraa lauseesta 4.

Tapauksessa  sarjan yleinen termi ei lähesty nollaa, joten sarja hajaantuu.

sarjan yleinen termi ei lähesty nollaa, joten sarja hajaantuu.

Viimeinen tapaus  ei sisällä mitään informaatiota (eikä myöskään todistettavaa).

ei sisällä mitään informaatiota (eikä myöskään todistettavaa).

Tämä tapaus esiintyy sekä harmonisen ( , hajaantuu!) että yliharmonisen (

, hajaantuu!) että yliharmonisen ( , suppenee!) sarjan kohdalla. Näissä tapauksissa suppenemista täytyy tutkia joillakin muilla menetelmillä, kuten aikaisemmin tehtiin.

, suppenee!) sarjan kohdalla. Näissä tapauksissa suppenemista täytyy tutkia joillakin muilla menetelmillä, kuten aikaisemmin tehtiin.

3. Jatkuvuus

Sisältö

- Funktion raja-arvo

- Raja-arvo ja jatkuvuus

- Jatkuvien funktioiden ominaisuuksia

Tässä luvussa määritellään funktion  raja-arvo pisteessä

raja-arvo pisteessä  . Oletamme, että lukija tuntee ennestään reaalimuuttujan funktion käsitteen ja lukujonon raja-arvon.

. Oletamme, että lukija tuntee ennestään reaalimuuttujan funktion käsitteen ja lukujonon raja-arvon.

Funktion raja-arvo

Olkoon  reaalilukujen osajoukko ja

reaalilukujen osajoukko ja  sellainen piste, että on olemassa jono pisteitä

sellainen piste, että on olemassa jono pisteitä  , joille

, joille  , kun

, kun  . Usein

. Usein  on kaikkien reaalilukujen joukko, mutta toisinaan myös väli (avoin, puoliavoin tai suljettu).

on kaikkien reaalilukujen joukko, mutta toisinaan myös väli (avoin, puoliavoin tai suljettu).

Esimerkki 1.

Pisteen  ei tarvitse kuulua joukkoon

ei tarvitse kuulua joukkoon  . Esimerkiksi jono

. Esimerkiksi jono  joukossa

joukossa ![S=\, ]0,2[ S=\, ]0,2[](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/5a611f94acc4b7abf3b85346aedbe506.gif) , kun

, kun  , ja

, ja  kaikilla

kaikilla  , mutta

, mutta  ei kuulu joukkoon

ei kuulu joukkoon  .

.

Toispuoleiset raja-arvot

Raja-arvon tärkeä ominaisuus on sen yksikäsitteisyys. Tämä tarkoittaa sitä, että tapauksessa  ja

ja  täytyy olla

täytyy olla  . Tästä huolimatta voi usein olla hyödyllistä tutkia funktion käyttäytymistä, kun

. Tästä huolimatta voi usein olla hyödyllistä tutkia funktion käyttäytymistä, kun  lähestyy tutkittavaa pistettä

lähestyy tutkittavaa pistettä  vain vasemmalta tai oikealta. Näitä kutsutaan funktion

vain vasemmalta tai oikealta. Näitä kutsutaan funktion  vasemman- tai oikeanpuoleisiksi raja-arvoiksi pisteessä

vasemman- tai oikeanpuoleisiksi raja-arvoiksi pisteessä  .

.

Määritelmä 2: Toispuoleiset raja-arvot

Olkoon  ja

ja  funktio, joka on määritelty (ainakin) joukossa

funktio, joka on määritelty (ainakin) joukossa  . Tällöin funktiolla

. Tällöin funktiolla  has a vasemmanpuoleinen raja-arvo

has a vasemmanpuoleinen raja-arvo  pisteessä

pisteessä  , merkitään

, merkitään

jos

jos  , kun

, kun  kaikille niille jonoille

kaikille niille jonoille  joukossa

joukossa

![S\cap ]-\infty,x_0[ =\{ x\in S : x < x_0 \} S\cap ]-\infty,x_0[ =\{ x\in S : x < x_0 \}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/c65f5d0e098970db4a09f85ad08fada6.gif) , joille

, joille  , kun

, kun  .

.

Vastaavasti funktiolla  on oikeanpuoleinen raja-arvo

on oikeanpuoleinen raja-arvo  pisteessä

pisteessä  , merkitään

, merkitään

, jos

, jos  , kun

, kun  kaikille niille jonoille

kaikille niille jonoille  joukossa

joukossa ![S\cap ]x_0,\infty[ =\{ x\in S : x_0 < x \} S\cap ]x_0,\infty[ =\{ x\in S : x_0 < x \}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/34e4590988ffbbcc84fe6f2077270c14.gif) , joille

, joille  , kun

, kun  .

.

Esimerkki 6.

Laskusääntöjä

Raja-arvojen laskusäännöt seuraavat suoraan vastaavista lukujonojen raja-arvon ominaisuuksista.

Raja-arvot ja jatkuvuus

Tässä kappaleessa määritellään funktion jatkuvuus. Jatkuvuuden intuitiivinen tulkinta on se, että funktion kuvaaja on yhtenäinen viiva. Tämä ei kuitenkaan ole matemaattisesti riittävän tarkka määritelmä, koska se mm. sisältää epämääräisiä (?) käsitteitä kuten "yhtenäinen" ja "viiva". Tämän perusteella voi esimerkiksi olla vaikea päättää, onko funktio  jatkuva vai ei.

jatkuva vai ei.

Esimerkki 1.

Esimerkki 2.

Olkoon  . Määritellään funktio

. Määritellään funktio  asettamalla

asettamalla

Silloin

Silloin

Tämän vuoksi

Tämän vuoksi  ei ole jatkuva pisteessä

ei ole jatkuva pisteessä  .

.

Seuraavaksi esitellään joitakin jatkuvien funktioiden perusominaisuuksia. Raja-arvosääntöjen avulla (Lause 2) saadaan:

Lause 3.

Jatkuvien funktioiden summa ja tulo ovat jatkuvia. Erityisesti polynomit ovat jatkuvia funktioita. Jos  ja

ja  ovat jatkuvia ja

ovat jatkuvia ja  , niin

, niin  on jatkuva pisteessä

on jatkuva pisteessä  .

.

Jatkuvien funktioiden yhdistetty funktio on jatkuva, kunhan se on määritelty:

Lause 4.

Olkoot  ja

ja  . Oletetaan, että

. Oletetaan, että  on jatkuva pisteessä

on jatkuva pisteessä  ja

ja  on jatkuva pisteessä

on jatkuva pisteessä  . Tällöin

. Tällöin  on jatkuva pisteessä

on jatkuva pisteessä  .

.

Huom. Jos  on jatkuva, niin

on jatkuva, niin  on jatkuva.

on jatkuva.

Miksi?

Huom. Jos  and

and  ovat jatkuvia, niin

ovat jatkuvia, niin  ja

ja  ovat jatkuvia. (Tässä

ovat jatkuvia. (Tässä  .)

.)

Miksi?

'}], {

strokeColor : colors[1],

fontSize : 16,

visible : false

});

l[2] = board.create('text', [-4, 3, function() { return '

'}], {

strokeColor : colors[1],

fontSize : 16,

visible : false

});

l[2] = board.create('text', [-4, 3, function() { return ' '}], {

strokeColor : colors[2],

fontSize : 16,

visible : false

});

g[0] = board.create('functiongraph', [f0, -6, 6], {

visible : true,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[0],

highlight : false

});

g[1] = board.create('functiongraph', [f1, -6, 6], {

visible : false,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[1],

highlight : false

});

g[2] = board.create('functiongraph', [f2, -6, 6], {

visible : false,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[2],

highlight : false

});

var currentGraph = g[0];

var currentLabel = l[0];

select.on('drag', function() {

currentGraph.setAttribute({ visible : false });

currentLabel.setAttribute({ visible : false });

currentGraph = g[select.Value()];

currentLabel = l[select.Value()];

currentGraph.setAttribute({ visible : true });

currentLabel.setAttribute({ visible : true, useMathJax : true });

select.setAttribute({ fillColor : colors[select.Value()] });

board.update();

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* Example 2. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox16', {

boundingbox : [-3.5, 4.5, 3.5, -1.25],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]]);

xaxis.removeAllTicks();

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

drawZero : true,

ticks : { majorHeight : 5, minorTicks : 0, ticksDistance : 1.0 }

});

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var xtick = board.create('segment', [[1, .05],[1, -.1]], {

strokeWidth : 1, strokeColor : 'black', strokeOpacity : .4,

highlight : false });

var f = function(x) { return 2; }

var g = function(x) { return 3; }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.5, 1], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [g, 1, 3.5], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('point', [1, f(1)], {

name : '',

fillColor : 'white',

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : .5,

size : 2,

fixed : true,

showInfobox : false

});

board.create('point', [1, g(1)], {

name : '',

fillColor : 'black',

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : .5,

size : 2,

fixed : true,

showInfobox : false

});

var x0 = board.create('text', [1, 0, function() { return '

'}], {

strokeColor : colors[2],

fontSize : 16,

visible : false

});

g[0] = board.create('functiongraph', [f0, -6, 6], {

visible : true,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[0],

highlight : false

});

g[1] = board.create('functiongraph', [f1, -6, 6], {

visible : false,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[1],

highlight : false

});

g[2] = board.create('functiongraph', [f2, -6, 6], {

visible : false,

strokeWidth : 1.5,

strokeColor : colors[2],

highlight : false

});

var currentGraph = g[0];

var currentLabel = l[0];

select.on('drag', function() {

currentGraph.setAttribute({ visible : false });

currentLabel.setAttribute({ visible : false });

currentGraph = g[select.Value()];

currentLabel = l[select.Value()];

currentGraph.setAttribute({ visible : true });

currentLabel.setAttribute({ visible : true, useMathJax : true });

select.setAttribute({ fillColor : colors[select.Value()] });

board.update();

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* Example 2. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox16', {

boundingbox : [-3.5, 4.5, 3.5, -1.25],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]]);

xaxis.removeAllTicks();

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

drawZero : true,

ticks : { majorHeight : 5, minorTicks : 0, ticksDistance : 1.0 }

});

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var xtick = board.create('segment', [[1, .05],[1, -.1]], {

strokeWidth : 1, strokeColor : 'black', strokeOpacity : .4,

highlight : false });

var f = function(x) { return 2; }

var g = function(x) { return 3; }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.5, 1], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [g, 1, 3.5], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('point', [1, f(1)], {

name : '',

fillColor : 'white',

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : .5,

size : 2,

fixed : true,

showInfobox : false

});

board.create('point', [1, g(1)], {

name : '',

fillColor : 'black',

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : .5,

size : 2,

fixed : true,

showInfobox : false

});

var x0 = board.create('text', [1, 0, function() { return ' '; }], {

useMathJax : true

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

'; }], {

useMathJax : true

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

Epsilon-delta määritelmä

Seuraavaksi esitetään jatkuvuuden  -määritelmä. Tärkein idea on se, että jos

-määritelmä. Tärkein idea on se, että jos  on jatkuva pisteessä

on jatkuva pisteessä  , niin funktion arvojen

, niin funktion arvojen  pitäisi lähestyä arvoa

pitäisi lähestyä arvoa  , kun

, kun  lähestyy pistettä

lähestyy pistettä  .

.

Tämä määritelmä yleistyy muillekin kuin tällä kurssilla käsitellyille reaalifunktioille.

Esimerkki 3.

', fillColor : '#bd4444', snapWidth : 0.01,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#bd4444', offset : [0, 25] }});

var x1 = board.create('glider', [1/2, 0, xaxis],

{ name: '

', fillColor : '#bd4444', snapWidth : 0.01,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#bd4444', offset : [0, 25] }});

var x1 = board.create('glider', [1/2, 0, xaxis],

{ name: ' ', strokeColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#446abd', offset : [5, 25] } });

/*board.suspendUpdate();*/

var y1 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X());}],

{ name : '

', strokeColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#446abd', offset : [5, 25] } });

/*board.suspendUpdate();*/

var y1 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X());}],

{ name : ' ', size : 2, strokeColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, fillColor : '#bd4444',

showinfobox : false, highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#bd4444', offset : [5, 25] }});

var y2 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X())-s.Value();}], { visible : false });

var y3 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X())+s.Value();}], { visible : false });

var z1 = board.create('point', [function(){return y1.Y()/4;}, function(){return y1.Y();}], { visible : false });

var z2 = board.create('point', [function(){return y2.Y()/4;}, function(){return y2.Y();}], { visible : false });

var z3 = board.create('point', [function(){return y3.Y()/4;}, function(){return y3.Y();}], { visible : false });

var v1 = board.create('segment', [z1, y1], { strokeColor : '#bd4444', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v2 = board.create('line', [z2, y2], { strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v3 = board.create('line', [z3, y3], { strokeColor: '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var epsilon = board.create('polygon', [function() { return [-.5, y2.Y()]; }, function() { return [2.5, y2.Y()]; },

function() { return [2.5, y3.Y()]; }, function() { return [-.5, y3.Y()]; }],

{ fillColor : '#bd4444', fillOpacity : .3, highlight : false, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }});

var h1 = board.create('segment', [function() { return x1; }, function() { return z1; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h2 = board.create('segment', [function() { return [z2.X(), 0]; },

function() { return [z2.X(), 8]}], { strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h3 = board.create('segment', [function() { return [z3.X(), 0]; },

function() { return [z3.X(), 8]}], { strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var delta = board.create('polygon', [h2.point1, h2.point2, h3.point2, h3.point1],

{ fillColor : '#446abd', fillOpacity : .3, highlight : false, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }});

var txt = board.create('text', [-2.5, .7, function() {

return '

', size : 2, strokeColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, fillColor : '#bd4444',

showinfobox : false, highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, strokeColor : '#bd4444', offset : [5, 25] }});

var y2 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X())-s.Value();}], { visible : false });

var y3 = board.create('point', [0, function(){return f(x1.X())+s.Value();}], { visible : false });

var z1 = board.create('point', [function(){return y1.Y()/4;}, function(){return y1.Y();}], { visible : false });

var z2 = board.create('point', [function(){return y2.Y()/4;}, function(){return y2.Y();}], { visible : false });

var z3 = board.create('point', [function(){return y3.Y()/4;}, function(){return y3.Y();}], { visible : false });

var v1 = board.create('segment', [z1, y1], { strokeColor : '#bd4444', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v2 = board.create('line', [z2, y2], { strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v3 = board.create('line', [z3, y3], { strokeColor: '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var epsilon = board.create('polygon', [function() { return [-.5, y2.Y()]; }, function() { return [2.5, y2.Y()]; },

function() { return [2.5, y3.Y()]; }, function() { return [-.5, y3.Y()]; }],

{ fillColor : '#bd4444', fillOpacity : .3, highlight : false, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }});

var h1 = board.create('segment', [function() { return x1; }, function() { return z1; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h2 = board.create('segment', [function() { return [z2.X(), 0]; },

function() { return [z2.X(), 8]}], { strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h3 = board.create('segment', [function() { return [z3.X(), 0]; },

function() { return [z3.X(), 8]}], { strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var delta = board.create('polygon', [h2.point1, h2.point2, h3.point2, h3.point1],

{ fillColor : '#446abd', fillOpacity : .3, highlight : false, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }});

var txt = board.create('text', [-2.5, .7, function() {

return ' '; }], {

strokeColor : '#446abd', useMathJax : true, fixed : true

});

/*board.unsuspendUpdate();*/

board.fullUpdate();

})();

'; }], {

strokeColor : '#446abd', useMathJax : true, fixed : true

});

/*board.unsuspendUpdate();*/

board.fullUpdate();

})();

Esimerkki 4.

Olkoon  . Määritellään funktio

. Määritellään funktio  asettamalla

asettamalla

Esimerkissä 2 nähtiin, että tämä funktio on epäjatkuva pisteessä

Esimerkissä 2 nähtiin, että tämä funktio on epäjatkuva pisteessä  . Tämän todistamiseksi

. Tämän todistamiseksi  -määritelmää käyttämällä täytyy löytää sellainen

-määritelmää käyttämällä täytyy löytää sellainen  ja

ja  , että kaikilla

, että kaikilla  on voimassa

on voimassa  , mutta

, mutta  .

.

Todistus. Olkoon  ja

ja  . Valitsemalla

. Valitsemalla  on voimassa

on voimassa

ja

ja

Näin ollen Lauseen 5 perusteella

Näin ollen Lauseen 5 perusteella  ei ole jatkuva pisteessä

ei ole jatkuva pisteessä  .

.

', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false, fixed : true,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#446abd' }});

board.suspendUpdate();

var x2 = board.create('point', [ function(){return x1.X()-s.Value();}, 0],

{ visible : false });

var x3 = board.create('point', [function(){return x1.X()+s.Value();},0],

{ visible : false });

var y1 = board.create('point', [-2, function() { return f(x1.X()); }],

{ size : 2, name: '

', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false, fixed : true,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#446abd' }});

board.suspendUpdate();

var x2 = board.create('point', [ function(){return x1.X()-s.Value();}, 0],

{ visible : false });

var x3 = board.create('point', [function(){return x1.X()+s.Value();},0],

{ visible : false });

var y1 = board.create('point', [-2, function() { return f(x1.X()); }],

{ size : 2, name: ' ', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#446abd' } });

var yd = board.create('point', [-2, function() { return f(x2.X()); }], {

size : 2, name: '

', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#446abd', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#446abd' } });

var yd = board.create('point', [-2, function() { return f(x2.X()); }], {

size : 2, name: ' ', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#bd4444', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#bd4444' }

});

/* doesn't really do anything atm... */

var dist = function() { if (Math.abs(f(x1)-f(x2.X())) != 0 || Math.abs(f(x1)-f(x3.X())) != 0) { return .5; } else { return 0; } };

var y2 = board.create('point', [0, function() {

return y1.Y()-dist(); }],

{ visible : false });

var y3 = board.create('point', [0, function() {

return y1.Y()+dist(); }],

{ visible : false });

var endpoint1 = board.create('point', [0, 2],

{ name : '', fixed : true, size : 2, fillColor : 'white', strokeWidth : .5, strokeColor : 'black', showinfobox : false });

var endpoint2 = board.create('point', [0, 3],

{ name : '', fixed : true, size : 2, fillColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, strokeColor : 'black', showinfobox : false });

var v1 = board.create('segment', [x1, function() { return [x1.X(), y1.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v2 = board.create('line', [x2, function() { return [x2.X(), x2.Y()+1]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v3 = board.create('line', [x3, function() { return [x3.X(), x3.Y()+1]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var delta = board.create('polygon', [function() { return [x2.X(), -5]; }, function() { return [x2.X(), 6]; },

function() { return [x3.X(), 6]; }, function() { return [x3.X(), -5]; }], {

highlight : false, fixed : true, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }, fillColor : '#446abd',

fillOpacity : .2

});

var h1 = board.create('segment', [y1, function() { return [x1.X(), y1.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h2 = board.create('line', [function() { return y2; }, function() { return [y2.X()+1, y2.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h3 = board.create('line', [function() { return y3; }, function() { return [y3.X()+1, y3.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var epsilon = board.create('polygon', [[-5, 3.5],[10, 3.5],[10, 2.5], [-5, 2.5]], {

highlight : false, fixed : true, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }, fillColor : '#bd4444',

fillOpacity : .2

});

var txt = board.create('text', [4.2, -1.5, function() {

return '

', strokeWidth : .3, strokeColor : 'black', fillColor : '#bd4444', showinfobox : false,

highlight : false,

label : { useMathJax : true, offset : [5, 25], strokeColor : '#bd4444' }

});

/* doesn't really do anything atm... */

var dist = function() { if (Math.abs(f(x1)-f(x2.X())) != 0 || Math.abs(f(x1)-f(x3.X())) != 0) { return .5; } else { return 0; } };

var y2 = board.create('point', [0, function() {

return y1.Y()-dist(); }],

{ visible : false });

var y3 = board.create('point', [0, function() {

return y1.Y()+dist(); }],

{ visible : false });

var endpoint1 = board.create('point', [0, 2],

{ name : '', fixed : true, size : 2, fillColor : 'white', strokeWidth : .5, strokeColor : 'black', showinfobox : false });

var endpoint2 = board.create('point', [0, 3],

{ name : '', fixed : true, size : 2, fillColor : 'black', strokeWidth : .5, strokeColor : 'black', showinfobox : false });

var v1 = board.create('segment', [x1, function() { return [x1.X(), y1.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v2 = board.create('line', [x2, function() { return [x2.X(), x2.Y()+1]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var v3 = board.create('line', [x3, function() { return [x3.X(), x3.Y()+1]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var delta = board.create('polygon', [function() { return [x2.X(), -5]; }, function() { return [x2.X(), 6]; },

function() { return [x3.X(), 6]; }, function() { return [x3.X(), -5]; }], {

highlight : false, fixed : true, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }, fillColor : '#446abd',

fillOpacity : .2

});

var h1 = board.create('segment', [y1, function() { return [x1.X(), y1.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#446abd', strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h2 = board.create('line', [function() { return y2; }, function() { return [y2.X()+1, y2.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var h3 = board.create('line', [function() { return y3; }, function() { return [y3.X()+1, y3.Y()]; }],

{ strokeColor : '#bd4444', dash : 2, strokeWidth : 1, highlight : false });

var epsilon = board.create('polygon', [[-5, 3.5],[10, 3.5],[10, 2.5], [-5, 2.5]], {

highlight : false, fixed : true, vertices : { visible : false }, borders : { visible : false }, fillColor : '#bd4444',

fillOpacity : .2

});

var txt = board.create('text', [4.2, -1.5, function() {

return ' '/*Math.max(Math.abs(y2.Y() - y1.Y()), Math.abs(y1.Y() - y3.Y())).toFixed(2)*/;

}], { strokeColor: '#bd4444', useMathJax : true, fixed : true });

board.unsuspendUpdate();

board.fullUpdate();

})();

'/*Math.max(Math.abs(y2.Y() - y1.Y()), Math.abs(y1.Y() - y3.Y())).toFixed(2)*/;

}], { strokeColor: '#bd4444', useMathJax : true, fixed : true });

board.unsuspendUpdate();

board.fullUpdate();

})();

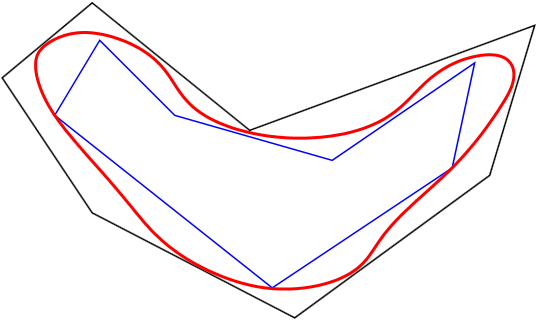

Jatkuvien funktioiden ominaisuuksia

Tässä kappaleessa tutustutaan jatkuvien funktioiden tärkeimpiin ominaisuuksiin. Aloitamme jatkuvien funktioiden väliarvolauseella, joka tunnetaan myös nimellä Bolzanon lause. Tämän lauseen erään muotoilun mukaan jatkuva funktio saa kaikki arvot sen maksimin ja minimin väliltä. Intuitiivinen perustelu on se, että jatkuvan funtion kuvaaja on yhtenäinen viiva.

Väliarvolause.

Esimerkki 1.

Esimerkki 2 (kummallinen?).

By the Intermediate Value Theorem we have  for

for  or

or  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  for

for  or

or  , because:

, because:

'}], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var fright = board.create('text', [9.1, 7.6, function() { return '

'}], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var fright = board.create('text', [9.1, 7.6, function() { return ' '}], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var xleft = board.create('text', [1.1, -.1, function() { return '

'}], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var xleft = board.create('text', [1.1, -.1, function() { return ' ' }], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var xright = board.create('text', [9.1, -.1, function() { return '

' }], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

var xright = board.create('text', [9.1, -.1, function() { return ' ' }], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

l.on('drag', function() {

if(l.point1.Y() >= 7) {

l.point1.moveTo([0, 7]);

l.point2.moveTo([1, 7]);

}

else if(l.point1.Y() <= 4) {

l.point1.moveTo([0, 4]);

l.point2.moveTo([1, 4]);

}

});

var intersections = [];

intersections[0] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 0], { name : '

' }], { strokeColor : 'black', fontSize : 13, fixed : true });

l.on('drag', function() {

if(l.point1.Y() >= 7) {

l.point1.moveTo([0, 7]);

l.point2.moveTo([1, 7]);

}

else if(l.point1.Y() <= 4) {

l.point1.moveTo([0, 4]);

l.point2.moveTo([1, 4]);

}

});

var intersections = [];

intersections[0] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 0], { name : ' ', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [0, -15], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

intersections[1] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 1], { name : '

', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [0, -15], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

intersections[1] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 1], { name : ' ', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [8, 22], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

intersections[2] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 2], { name : '

', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [8, 22], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

intersections[2] = board.create('intersection', [l, g, 2], { name : ' ', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [0, -15], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

board.unsuspendUpdate();

})();

/* Example 1. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox17', {

boundingbox : [-3.5, 2.5, 3.5, -3.5],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var f = function(x) { return (Math.pow(x,5)-3*x-1); }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.5, 3.5], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* Example 2. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox18', {

boundingbox : [-3.2, 2.9, 3.2, -2.9],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var f = function(x) { return (x*x*x-x); }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.2, -1], {

strokeColor : 'blue',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -1, 0], {

strokeColor : 'red',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, 0, 1], {

strokeColor : 'blue',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, 1, 3.2], {

strokeColor : 'red',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

', showinfobox : false,

label : { fontSize : 13, offset : [0, -15], strokeColor : 'blue', strokeWidth : .5} });

board.unsuspendUpdate();

})();

/* Example 1. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox17', {

boundingbox : [-3.5, 2.5, 3.5, -3.5],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var f = function(x) { return (Math.pow(x,5)-3*x-1); }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.5, 3.5], {

strokeColor : 'black',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

/* Example 2. */

(function() {

var board = JXG.JSXGraph.initBoard('jxgbox18', {

boundingbox : [-3.2, 2.9, 3.2, -2.9],

showcopyright : false,

shownavigation : false});

var xaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [1, 0]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

var yaxis = board.create('axis', [[0, 0], [0, 1]], {

ticks : { majorHeight : 7, minorTicks : 0, drawZero : true }

});

xaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

yaxis.defaultTicks.ticksFunction = function() { return 1; };

var f = function(x) { return (x*x*x-x); }

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -3.2, -1], {

strokeColor : 'blue',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, -1, 0], {

strokeColor : 'red',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, 0, 1], {

strokeColor : 'blue',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.create('functiongraph', [f, 1, 3.2], {

strokeColor : 'red',

strokeWidth : 2,

highlight : false

});

board.fullUpdate();

})();

Seuraavaksi osoitetaan, että suljetulla välillä jatkuva funktio on rajoitettu. Tässä on tärkeää, että kyseessä on nimenomaan suljettu väli. Lauseen jälkeinen esimerkki osoittaa, ettei väite pidä paikkaansa avoimille väleille.

Huom. Jos ![f\colon ]a,b[\to \mathbb{R} f\colon ]a,b[\to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/b877964696acedfc796cbe2d8af02c14.gif) on jatkuva, niin se ei välttämättä ole rajoitettu.

on jatkuva, niin se ei välttämättä ole rajoitettu.

Esimerkki 4.

Esimerkki 5.

Olkoon ![f\colon [-1,2] \to \mathbb{R} f\colon [-1,2] \to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/7e4a05522be3c7dbc56233602cd169af.gif) ,

,

Funktion määrittelyjoukko on

Funktion määrittelyjoukko on ![[-1,2] [-1,2]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/939b17134a44bb821e6c01efd044b32e.gif) . Funktion arvojoukon määrittämiseksi osoitetaan ensin, että funktio on vähenevä.

. Funktion arvojoukon määrittämiseksi osoitetaan ensin, että funktio on vähenevä.

Koska  ,

niin

,

niin  ja

ja

Näin ollen oletuksesta

Näin ollen oletuksesta  seuraa

seuraa  , joten funktio

, joten funktio  on vahenevä.

on vahenevä.

Vähenevän funktion minimiarvo on välin päätepisteessä. Näin ollen funktion ![f:[-1,2] \to \mathbb{R} f:[-1,2] \to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/46f6b5865e82341801d84f074d5275a9.gif) minimi on

minimi on

Vastaavasti suurin arvo on väli alkupisteessä, joten funktion

Vastaavasti suurin arvo on väli alkupisteessä, joten funktion ![f:[-1,2] \to \mathbb{R} f:[-1,2] \to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/46f6b5865e82341801d84f074d5275a9.gif) maksimi on

maksimi on

Polynomina funktio  on jatkuva, joten se saa kaikki arvot maksimin ja minimin välillä. Näin ollen funktion

on jatkuva, joten se saa kaikki arvot maksimin ja minimin välillä. Näin ollen funktion  arvojoukko on

arvojoukko on ![[-7, 5] [-7, 5]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/e8699196563455925f438ba7d4253294.gif) .

.

Esimerkki 6.

Olkoon  polynomi. Silloin

polynomi. Silloin  on jatkuva joukossa

on jatkuva joukossa  ja lauseen 7 nojalla myös rajoitettu jokaisella suljetulla välillä

ja lauseen 7 nojalla myös rajoitettu jokaisella suljetulla välillä ![[a,b] [a,b]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.gif) , kun

, kun  . Lauseen 3 perusteella funktiolla

. Lauseen 3 perusteella funktiolla  on maksimi ja minimi

on maksimi ja minimi ![[a,b] [a,b]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.gif) .

.

Huom. Lause 8 liittyy väliarvolauseeseen seuraavalla tavalla:

Jos ![f\colon [a,b]\to \mathbb{R} f\colon [a,b]\to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/fb88b7c4cd82a1b35ba68754b552ae78.gif) on jatkuva, niin on olemassa pisteet

on jatkuva, niin on olemassa pisteet ![x_1,x_2\in [a,b] x_1,x_2\in [a,b]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/e19d698696d7ffab6b38c33a403d0f82.gif) , joille funktion arvojoukko on muotoa

, joille funktion arvojoukko on muotoa ![f([a,b])=[f(x_1),f(x_2)] f([a,b])=[f(x_1),f(x_2)]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/d38dd7ed255a633b5f3b32a8b4251475.gif) .

.

4. Derivaatta

Sisältö

- Derivaatta

- Derivaatan ominaisuudet

- Trigonometristen funktioiden derivaatat

- Ketjusääntö

- Ääriarvot

Derivaatta

Tässä luvussa käsitellään derivaattaa ja sen ominaisuuksia. Aloitetaan esimerkillä, joka johdattelee derivaatan määritelmää.

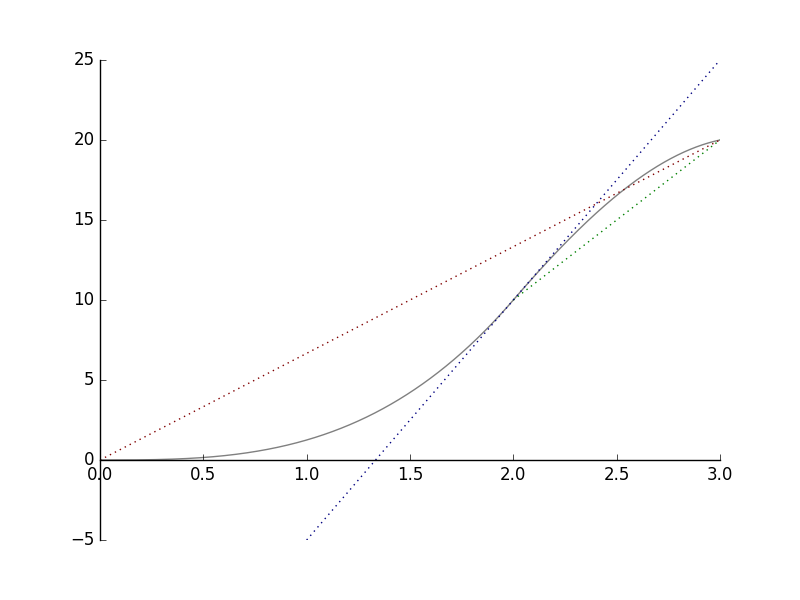

Esimerkki 0.

Alla oleva kuvaaja kertoo, kuinka kauaksi pyöräilijä on edennyt lähtöpisteestään.

a) Tarkastellaan punaista viivaa. Huomataan, että kolmen tunnin aikana pyöräilijä on edennyt  km. Hänen keskinopeutensa on

km. Hänen keskinopeutensa on  km/h.

km/h.

b) Tarkastellaan sitten vihreää viivaa. Huomataan, että kolmannen tunnin aikana pyöräilijä on edennyt  km. Tällä aikavälillä hänen keskinopeutensa on siis

km. Tällä aikavälillä hänen keskinopeutensa on siis  km/h.

km/h.

Huomaa, että punaisen viivan kulmakerroin on  ja vihreän viivan kulmakerroin on

ja vihreän viivan kulmakerroin on  . Lukuarvot ovat samat kuin vastaavat keskinopeudet.

. Lukuarvot ovat samat kuin vastaavat keskinopeudet.

c) Tarkastellaan vielä sinistä viivaa. Se on kuvaajan tangentti kohdassa  h. Kuten keskinopeuksien kohdalla, voidaan päätellä, että kaksi tuntia lähdön jälkeen pyöräilijän nopeus oli

h. Kuten keskinopeuksien kohdalla, voidaan päätellä, että kaksi tuntia lähdön jälkeen pyöräilijän nopeus oli  km/h

km/h  km/h.

km/h.

Siirrytään sitten yleiseen määritelmään:

Määritelmä: Derivaatta

Olkoon  . Funktion

. Funktion  derivaatta pisteessä

derivaatta pisteessä  on

on  Jos

Jos  on olemassa, niin

on olemassa, niin  on derivoituva pisteessä

on derivoituva pisteessä  .

.

Huom: Koska  , niin

, niin  , joten määritelmä voidaan kirjoittaa myös muodossa

, joten määritelmä voidaan kirjoittaa myös muodossa

Tulkinta. Tarkastellaan käyrää  . Jos piirretään suora viiva pisteiden

. Jos piirretään suora viiva pisteiden  ja

ja  kautta, niin tämän suoran kulmakerroin on

kautta, niin tämän suoran kulmakerroin on  Kun

Kun  , tämä suora sivuaa käyrää

, tämä suora sivuaa käyrää  pisteessä

pisteessä  . Tämä suora on käyrän

. Tämä suora on käyrän  tangentti pisteessä

tangentti pisteessä  ja sen kulmakerroin on

ja sen kulmakerroin on  joka on funktion

joka on funktion  derivaatta pisteessä

derivaatta pisteessä  . Tangentin yhtälö on siis muotoa

. Tangentin yhtälö on siis muotoa

Kokeile. Tutki tangentin muuttumista siirtämällä sivuamispistettä.

Esimerkki 1.

Esimerkki 2.

Esimerkki 3.

Olkoon  ,

,  . Onko

. Onko  derivoituva pisteessä

derivoituva pisteessä  ?

?

Kuvaajalla  ei ole tangenttia pisteessä

ei ole tangenttia pisteessä  :

:  Näin ollen

Näin ollen  ei ole olemassa.

ei ole olemassa.

Johtopäätös. Funktio  ei ole derivoituva pisteessä

ei ole derivoituva pisteessä  .

.

Huom. Olkoon  . Jos

. Jos  on olemassa kaikissa pisteissä

on olemassa kaikissa pisteissä  , niin saadaan uusi funktio

, niin saadaan uusi funktio  . Merkitään:

. Merkitään:

| (1) |  |

=  , , |

|

| (2) |  |

=  |

=  , , |

| (3) |  |

=  |

=  , , |

| (4) |  |

=  |

=  , , |

| ... |

Tässä  on funktion

on funktion  toisen kertaluvun derivaatta pisteessä

toisen kertaluvun derivaatta pisteessä  ,

,  on kolmannen kertaluvun derivaatta jne.

on kolmannen kertaluvun derivaatta jne.

Yleisesti merkitään \begin{eqnarray} C^n\bigl( ]a,b[\bigr) =\{ f\colon \, ]a,b[\, \to \mathbb{R} & \mid & f \text{ on } n \text{ kertaa derivoituva välillä } ]a,b[ \nonumber \\ & & \text{ ja } f^{(n)} \text{ on jatkuva}\}. \nonumber \end{eqnarray} Tällaiset funktiot ovat n kertaa jatkuvasti derivoituvia.

Esimerkki 4.

Linearisointi ja differentiaali

missä oikean puolen lauseke on funktion

missä oikean puolen lauseke on funktion  linearisointi tai differentiaali pisteessä

linearisointi tai differentiaali pisteessä  . Differentiaalia merkitään

. Differentiaalia merkitään  . Linearisoinnin kuvaaja

. Linearisoinnin kuvaaja  on funktion kuvaajan tangentti pisteessä

on funktion kuvaajan tangentti pisteessä  . Differentiaalin varsinainen merkitys tulee näkyviin vasta usean muuttujan funktioiden yhteydessä, eikä sitä tarvita tällä kurssilla.

. Differentiaalin varsinainen merkitys tulee näkyviin vasta usean muuttujan funktioiden yhteydessä, eikä sitä tarvita tällä kurssilla.Derivaatan ominaisuudet

Seuraavaksi käydään läpi derivaatan tärkeimmät ominaisuudet. Näiden avulla voidaan selvittää tärkeimpien alkeisfunktioiden derivaatat.

Jatkuvuus ja derivaatta

Derivointisäännöt

For  we repeteadly apply the product rule, and obtain

we repeteadly apply the product rule, and obtain

The case of negative  is obtained from this and the product rule applied to the identity

is obtained from this and the product rule applied to the identity  .

.

From the power rule we obtain a formula for the derivative of a polynomial. Let  where

where  . Then

. Then

Suppose that  is differentiable at

is differentiable at  and

and  . We determine

. We determine

From the definition we obtain:

The one-sided limits of the difference quotient have different signs at a local extremum. For example, for a local maximum it holds that \begin{eqnarray} \frac{f(x_0+h)-f(x_0)}{h} = \frac{\text{negative} }{\text{positive}}&\le& 0, \text{ when } h>0, \nonumber \\ \frac{f(x_0+h)-f(x_0)}{h} = \frac{\text{negative}}{\text{negative}}&\ge& 0, \text{ when } h<0 \nonumber \end{eqnarray} and  is so small that

is so small that  is a maximum on the interval

is a maximum on the interval ![[x_0-h,x_0+h] [x_0-h,x_0+h]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/fa82e5aaac1e1a7465724ab32e282839.gif) .

.

Trigonometristen funktioiden derivaatat

Tässä kappaleessa johdetaan funktioiden  ,

,  ja

ja  derivaatat.

derivaatat.

Ketjusääntö

Ketjusäännöllä tarkoitetaan yhdistettyjen funktioiden derivoimissääntöä. Tämä termin tausta selittyy paremmin usean muuttujan funktioiden (osittais)derivaattojen yhteydessä.

Ketjusääntö.

Todistus.Esimerkki 1.

Esimerkki 2.

Esimerkki 3.

Ääriarvot

Tässä kappaleessa tarkastellaan derivaatan käyttöä ääriarvotehtävissä.

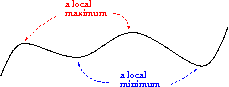

Määritelmä: Paikallinen maksimi ja minimi

Funktiolla  on paikallinen maksimi pisteessä

on paikallinen maksimi pisteessä  , jos on olemassa sellainen

, jos on olemassa sellainen  , että

, että  aina kun

aina kun  ja

ja  .

.

Vastaavasti, funktiolla  on paikallinen minimi pisteessä

on paikallinen minimi pisteessä  , jos on olemassa sellainen

, jos on olemassa sellainen  , että

, että  aina kun

aina kun  ja

ja  .

.

Funktion paikallinen ääriarvo tarkoittaa joko paikallista maksimia tai paikallista minimiä.

Huom. Jos  on paikallinen maksimikohta ja

on paikallinen maksimikohta ja  on olemassa, niin

on olemassa, niin

Näin ollen

Näin ollen  .

.

Näin saadaan:

Esimerkki 1.

Globaali maksimi ja minimi

Käytännössä paikallisia ääriarvoja voi esiintyä kolmea eri tyyppiä olevissa pisteissä:

derivaatan nollakohdat

määrittelyvälin päätepisteet

määrittelyvälin sisällä olevat kohdat, joissa funktio ei ol e derivoituva

Jos tiedetään etukäteen, että funktiolla on maksimi tai minimi, niin aluksi etsitään kaikki mahdolliset paikalliset ääriarvokohdat (yllä oleva lista), lasketaan funktion arvot näissä pisteissä ja valitaan näistä arvoista suurin tai pienin.

Esimerkki 2.

Määritetään funktion ![f\colon [0,2]\to \mathbf{R} f\colon [0,2]\to \mathbf{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/ee77c8a9721b9494f327d61422eb2068.gif) ,

,  , suurin ja pienin arvo. Koska kyseessä on suljetulla välillä jatkuva funktio, niin sillä on maksimi ja minimi. Funktio on myös derivoituva, joten riittää tutkia välin päätepisteet ja välin sisälle jäävät derivaatan nollakohdat.

, suurin ja pienin arvo. Koska kyseessä on suljetulla välillä jatkuva funktio, niin sillä on maksimi ja minimi. Funktio on myös derivoituva, joten riittää tutkia välin päätepisteet ja välin sisälle jäävät derivaatan nollakohdat.

Derivaatan nollakohdat:  . Koska

. Koska ![-\sqrt{2}\not\in [0,2] -\sqrt{2}\not\in [0,2]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/601d5044bf746b9e7af4678c2c3463a1.gif) , täytyy laskea funktion arvot vain kolmessa pisteessä:

, täytyy laskea funktion arvot vain kolmessa pisteessä:  ,

,  ja

ja  . Näiden avulla päätellään funktion pienimmäksi arvoksi

. Näiden avulla päätellään funktion pienimmäksi arvoksi  ja suurimmaksi arvoksi

ja suurimmaksi arvoksi  .

.

Seuraavaksi esitetään eräs tärkeimmistä derivoituvia funktioita koskevista tuloksista.

Lause 2.

(Derivoituvien funktioiden väliarvolause). Olkoon ![f\colon [a,b]\to \mathbb{R} f\colon [a,b]\to \mathbb{R}](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/fb88b7c4cd82a1b35ba68754b552ae78.gif) jatkuva suljetulla välillä

jatkuva suljetulla välillä ![[a,b] [a,b]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.gif) ja derivoituva avoimella välillä

ja derivoituva avoimella välillä  . Silloin

. Silloin

jollekin

jollekin

Let  be continuous in the interval

be continuous in the interval ![[a,b] [a,b]](https://mycourses.aalto.fi/filter/tex/pix.php/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.gif) and differentiable in the interval

and differentiable in the interval  . Let us define

. Let us define

Now  and

and  is differentiable in the interval

is differentiable in the interval  . According to Rolle's Theorem, there exists

. According to Rolle's Theorem, there exists  such that

such that  . Hence

. Hence

Tärkeitä seurauksia:

Lause 3.

Esimerkki 3.

Esimerkki 4.

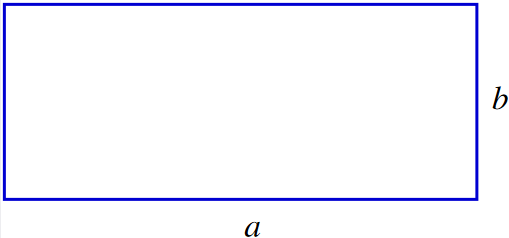

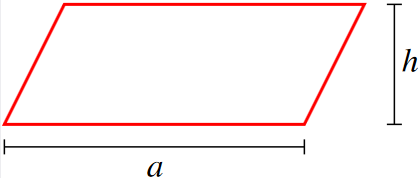

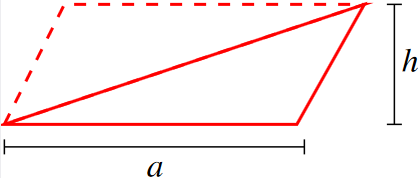

Määritetään sellainen suorakulmio, jonka pinta-ala on  ja jonka piiri on mahdollisimman pieni.

ja jonka piiri on mahdollisimman pieni.

Olkoot  ja

ja  suorakulmion sivut. Silloin

suorakulmion sivut. Silloin  , joten

, joten  . Suorakulmion piiri on

. Suorakulmion piiri on

Etsitään funktion

Etsitään funktion  pienin arvo. Funktio

pienin arvo. Funktio  on derivoituva, kun

on derivoituva, kun  , ja osamäärän derivoimissäännön mukaan

, ja osamäärän derivoimissäännön mukaan

Nyt

Nyt  , kun

, kun

mutta ehdon

mutta ehdon  perusteella vain

perusteella vain  on mahdollinen. Muodotetaan kulkukaavio:

on mahdollinen. Muodotetaan kulkukaavio:

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

väh. | kasv. |

Koska funktio  on jatkuva, niin se saavuttaa miniminsä pisteessä

on jatkuva, niin se saavuttaa miniminsä pisteessä  . Tällöin sen toisen sivun pituus on

. Tällöin sen toisen sivun pituus on  .

.

Esimerkki 5.

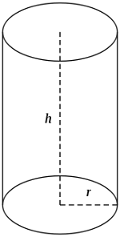

Tehtävänä on muodostaa suoran ympyräsylinterin muotoinen yhden litran mitta (ilman kantta) niin, että materiaalia tarvitaan mahdollisimman vähän.

Olkoon  sylinterin poikkileikkauksen säde ja

sylinterin poikkileikkauksen säde ja  sylinterin korkeus. Sylinterin tilavuus on

sylinterin korkeus. Sylinterin tilavuus on  dm

dm , joten saadaan yhtälö

, joten saadaan yhtälö  . Tästä voidaan ratkaista