25C00100 - Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 01.11.2018-22.11.2018

This course space end date is set to 22.11.2018 Search Courses: 25C00100

Glossary

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

$ |

|---|

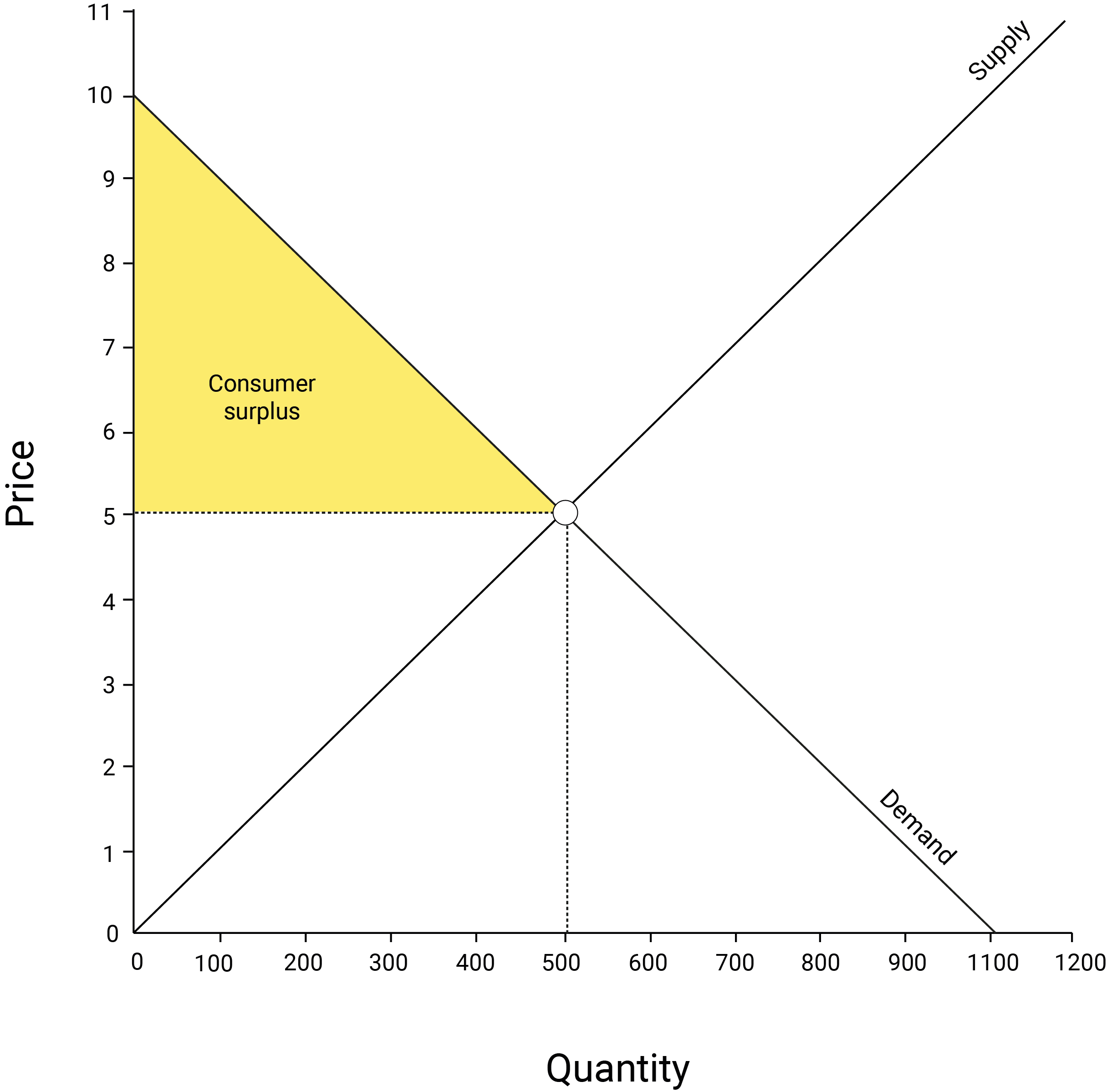

$4 and $3If the customer values a pint of Jane’s beer at $9 and pays $5 for it, they have ‘saved’ $4 that they would have happily spent. This is their consumer surplus. | ||

A |

|---|

alcopopReally? You don't know what alcopops are? OK, here we go ! | ||

B |

|---|

B – CRemember the formula for value creation: value created = benefits perceived by the consumer (B) – the costs incurred by the producer (C). | ||

C |

|---|

consumer surplusConsumer

surplus is generated when the consumer feels that they get more benefit (B) out

of the product compared to the price (P) that they pay to obtain it. Consumer

surplus occurs when B – P > 0. The market equilibrium price denotes B – P =

0. All points in the demand curve to the left of the equilibrium denote B – P >

0, or consumer surplus.

| ||

contract brewRead more about contract brewing here. | ||

D |

|---|

demand curveDemand curve depicts the consumers’ maximum willingness to pay: how many units of the product are consumers willing to buy at a given price. This curve is downward sloping: consumers are generally willing to buy more when the price is low. On a market level, this means that there are more consumers willing to buy the product if the price is low, compared to when the price is high.

| ||

duopoly equilibriumThe following explanation of how the duopoly equilibrium quantities were derived is for those interested – learning all the computations is not necessary to complete the course.

The duopoly price and quantities are based on insights from the so-called Cournot duopoly model. According to this model, the profit-maximising equilibrium outcome for two identical firms – which we assume Jane and Emma to run because they have identical cost structures and sell a homogeneous product – is to produce equal quantities. These two quantities jointly clear the market, meaning that the price is lowered until all that is produced is sold.

The following explains how the equilibrium price and quantity were determined. Emma’s profit (Π) function is as follows:

ΠEmma = Revenue – Total cost = P*QEmma – TCEmma = (100 – QEmma – QJane)QEmma – (800 + 10QEmma) = 100QEmma – QEmma2 – QEmma*QJane – 800 – 10QEmma = 90QEmma – QEmma2 – QEmma*QJane – 800

Emma maximises her profit by (we treat QJane as a constant):

∂ΠEmma/∂QEmma = 90 – 2QEmma – QJane 90 – 2QEmma – QJane = 0 -2QEmma = -90 + QJane QEmma = 45 – 0.5QJane

The final equation is Emma’s reaction function. It gives Emma’s best response to whatever quantity Jane chooses to produce (QJane). Because Jane’s firm is identical to Emma’s, her reaction function is QJane = 45 – 0.5QEmma.

Based on the reaction functions, we can solve the market clearing (equilibrium) quantity as follows:

QEmma = 45 – 0.5(45 – 0.5QEmma) QEmma = 45 – 22.5 – 0.25QEmma 0.75QEmma = 22.5 QEmma = 30

Because Jane’s reaction function is a mirror image of Emma’s, the resulting quantity would be the same. Thus, in a Cournot duopoly equilibrium, Emma and Jane would choose to produce 30 casks of beer each which results in a market price of (P = 100 – 30 – 30) of $40. | ||

E |

|---|

equilibriumYou can read more about market equilibrium here. | ||

F |

|---|

fundamental transformationOliver Williamson refers to this as fundamental transformation: before investing in relationship-specific assets, the buyer can buy from any number of competing sellers (a ‘large numbers’ bargaining situation); after the investment, buying from anyone else than the current seller incurs an additional cost known as the switching cost (a ‘small numbers’ bargaining situation). | ||